Like every girl, I enjoy a good love story.

However, this one was different.

As children growing up in Kerala, Marcus and Annamma Chacko lived just five kilometers apart. Their communities never intermingled. Marcus explains, "Though we hail from the same place, her people and my people had nothing much to do with each other because we belonged to two different castes."

They finally met in Uttar Pradesh. Marcus was a guest singer at a music hall where Annamma was in the audience. She instantly felt an affinity to Marcus when he sang in their mother tongue, Malayalam. After a three-minute conversation, they parted ways.

Two years later they ran into each other again while working for the same nonprofit organization. Though in separate departments, they couldn't help but admire each other's warmth, energy, and passion for social justice.

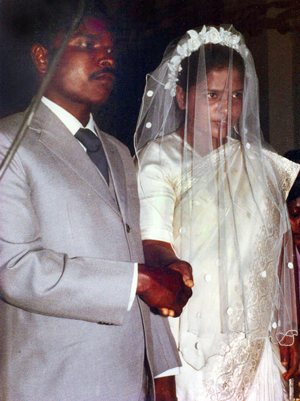

Marcus and Annamma Chacko Wedding Photos

Mutual friends noticed their compatibility and offered to arrange a marriage, but they resisted. Marcus recalls, "Elders in the organization proposed her to me but I told them, that this will never work as we are both from different castes.'" Marcus' leaders promised they would defend Annamma and Marcus if caste was the main issue and that they would legally fight for them, as the Indian constitution allows inter-caste marriage."

Not wanting to go against their parents, Marcus and Annamma waited for familial support, but to no avail. Annamma's high caste family remained furious at the prospect of her marriage to a Dalit. Marcus was simply not an option.

In the end however, Marcus and Annamma consented to their arranged marriage.

Friends provided food, decor, and beautiful wedding saris, but the couple recalls, "We had to struggle through uncertainties, threats and isolation from immediate family members."

Through their marriage, Annamma exchanged her family's stature and community for Marcus' life of humility and simplicity.

Marcus and Annamma Chacko Wedding Photos

By marrying outside of their caste-base communities the Chacko's broke a cardinal imperative of Indian socio-matrimonial conventions. Namely, whether arranged by friends as was the Chacko’s marriage, or arranged by family members as are many traditional Indian marriages, TIME South Asia bureau Chief Jyoti Thottam writes that the basic premise of an arranged marriage is that one should marry within one's own community.

The Continued Desirability of Arranged Marriages

Arranged marriages are still desirable to many (even westernized) Indians for a variety of reasons. After surveying over 130 US-based Indian university students in the spring of 2007, some reasons that particularly stood out to me were:

1) For the technologically savvy Generations X and Y, the nayan or matchmaker, is now a machine.

Gone are the days of awkward, stifling, über-controlled visits with prospective spouses in their parents' homes. The ability to size up candidates is now just a mouse-click away. The Indian Diaspora has been quick to catch on to this newfound convenience. The world's largest Indian matrimonial website currently boasts 800,000+ successes. These are often considered arranged marriages, since relatives can create the profiles.

2) The process and definition of an "arranged marriage" has changed. The "arranged-love-marriage" is a rapidly growing phenomenon among urban Indians.

Parents find or approve noteworthy candidates and then give their children the freedom to veto them or meet via "internet cafes" and even real cafes, leading to a quasi-courtship.

3) The very nature of globalization heightens the desire to return to Indian roots.

In the global conglomeration of cultures, people yearn for communities to which they truly belong. Prospective spouses who value their heritage and will pass it on to future generations are especially desirable.

4) The high divorce rate in the West, combined with the strong Indian stigma of divorce, makes Indians cautious of love-matches. The general consensus is that "love marriages" which are often "based on emotions" are unreliable. In an arranged marriage, the couple is held accountable to extended families on both sides. While increasing pressure, this brings an enormous level of community and family support, decreasing the likelihood of divorce.

However there are those who don't agree with arranged marriages. Sunita Rodricks is a Chicago-based Indian who still values much of the Indian culture, but opted for a love-marriage rather than an arranged one. In doing so, she escaped some of the more negative aspects of arranged marriages.

In explaining her reservations with caste-based arranged marriages, Rodricks says, "You can live anywhere in the world and profess to be really broadminded, but when it comes to your kith and kin, things don't change. Caste matters, not just being a Hindu but also being from the proper gotr (sect)."

She defends love-marriages like her own by arguing that, "A love marriage is a different matter: here the caste, skin color and dowry don't count. More and more people are opting to choose their own spouses but acceptance of such marriages is hard and takes time with the family."

Simran Mathew, an Indian model living in Dubai, couldn't agree more. She says that the "caste system plays a very important role in a Hindu family's life. I disagree with this whole tradition." She continues, "To me it's like a family basically putting their daughter up for sale, which is sad for a young girl to go through. And I am sure this whole thing goes on all over the world and not just in Dubai where there is a huge population of Indians. But times have changed and I believe this generation is getting bolder, and are voicing their opinion to the families."

Indeed, many young people would prefer if caste, skin color, and the dowry-system were frozen into their parents' history books and left out of their contemporary lives.

Caste Threatens Today's Arranged Marriages

Like a stubborn stain on a prized carpet, the caste system just won't seem to wipe off of the Indian landscape. It continues to haunt India for generations. To illustrate, I created two "marriage profiles" on a high traffic arranged marriage website, being careful to omit my surname in order to conceal my identity.

In the first profile I posed as a well-educated Dalit living in the US. In the second profile I included the same interests, physical descriptions, and "biodata" that I used in my Dalit profile. I changed only one detail: I listed my caste as "Brahmin."

My first (Dalit) profile received 23 interests in the first three days; 80% of men who viewed my profile did not express an interest. My second (Brahmin) profile got hundreds of hits from around the world within the first day. In fact, my profile became so inundated with messages that I quickly decided to close it down. I still had to deal with my 23 Dalit-profile hits. I emailed them, "Thank you for your interest in my profile. By the way, I am listed as a Dalit. Is this a problem for you or your family?" No one contacted me back. Those who had shown interest in my profile must have not noticed my posted caste; once I pointed it out to them they were no longer interested.

Clearly, among internet-surfing Indians, caste still matters...a lot.

The Economics of Inter-Caste Marriages

"Matrimonials" websites like the one I used above can easily, even unintentionally, keep lower castes out, simply by featuring membership rates upwards of US $100 per month. This is more than one-month's salary for most Indians. As the Wall Street Journal recently reported, the average Indian still makes around $1000 a year. India's 300 million Dalits largely represent this underpaid quota.

In addition to the expenses of going digital, the phone bills resulting from today's global arranged marriages can be staggering. Thottam recounts how a young risk management consultant, who was born in India but grew up in Singapore and found her husband on matrimonials.com, flew to India to marry him after "spending four months and US $8,000 in phone bill courting."

Then comes the wedding itself. According' to Reuters India, the average cost of a standard Indian wedding is between Rs 3 lakh ($7,500) and Rs 6 lakh ($15,000), which is the equivalent of up to 15 times the average Indian salary. However, the growing middle classes of India often host weddings in the upper $20,000s and $30,000s, and upper castes in the millions.

Of course, none of these quotes include the dowry.

Globalization, Dowry, and the Dalits

"Dowry?" you may ask. "Hasn't that long been outlawed?"

Well, yes it has. But social-snobbery and materialistic greed are just the ingredients that India's dowry system needed in order to come back with a vengeance.

The frequency of dowry-deaths is growing, thanks to a rise in India's materialism. In 2001, TIME magazine reported that dowry-deaths had grown from 400 a year in the mid-1980s to nearly 6,656 a year in the mid-1990s.

Ten years later in 2005, India's National Crime Record Bureau recorded at least one reported dowry death every 77 minutes, equaling c. 7,000 dowry deaths in the year.

However, most dowry deaths are framed as accidents and are not investigated, so the official statistics are expected to be much greater.

Abigail Lavin of The Weekly Standard explains that there is a strong correlation between the rise in dowry-related violence and India's economic boom since India opened to foreign investment in 1990. According to Lavin, analysts say that, "The country's growing economy exacerbates dowry crimes by encouraging a culture of materialism."

"For many in India's growing middle class, newfound prosperity has brought with it the lure of conspicuous consumption. Lavish dowry payments are seen as a way to increase a family's stockpile of luxury items and brand-name goods," she says.

In short, dowry is the easy way to ride India's wave of the nuvo riche.

So what does dowry have to do with the Dalits?

John Paulraj, an Indian urban single living in Delhi, has witnessed again and again the contemporary usage of dowry, even in the marriages of his close friends.

He explains that there is a strong correlation between caste-consciousness and dowry-related atrocities. "Whenever I think about caste, it's a status symbol," he says. "It has to do with social status...and the reason they don't want to marry a lower caste person has to do with the low dowry and low status. Caste matters a lot, but if the Dalit is wealthy, this could make up for it."

But even if a Dalit has managed to stay in school and acquire a good education, to get hired for a decently paying job, and to make enough money to be accepted as eligible for a decent marriage and dowry, she may not live past her wedding day.

A Traditional Indian Wedding In Los Angeles, CA USA

Wedding Crashers in India

While comedies feature wedding crashing as a lighthearted topic, this past February the Times of India reported a shocking case of wedding crashing in Haryana, where eleven upper-caste men crashed the wedding of a Dalit's daughter.

Not only was the wedding party beaten and robbed, but the property of the Dalit family was burned. As their land went up in flames, caste-based insults condemned them for their 'excessive' display of wealth (the groom had ridden in on a ghodi or horse).

With the Times of India, Dalit intellectual Chandrabhan Prasad explained that "Riding a horse carriage during a wedding [showcases the couple's] newfound upward mobility."

Prasad has sited this trend of caste-based wedding revolts not only in Haryana but also in Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan.

Globalization Hasn't Changed Caste Based Arranged Marriages . . . Yet

A wise sociologist once mused that we must choose our mothers carefully. The year 2009 finds us in an increasingly global society. Yet to a large extent the rung of our birth still shapes the quality of our education, careers, medical care, life expectancy, and choice of spouse.

Talk of India's economic and technological advancements certainly reflects truth, but it does not represent the full picture. Enchantment with India's elegant global rise masks a darkly shadowed backstage, where injustices still persist in the names of caste and downright indifference.

But until now, it seems like most of us would rather keep silent, than to disrupt our lovely little bubbles of comfort. Our caste-based identity disorder has yet to be abolished, even in sophisticated online settings.

As a friend once shared with me over a chai, "I often wonder, what would I do if I were growing up in Nazi Germany? Would I just go along with it all, like all the others around me, and not trying to figure out what was really going on behind the scenes? And assuming I did care enough to find out, what then? Would I defend the Jews? Or would I just keep silent..."

She paused and then continued, "Well I'm not a girl in Nazi Germany, but I am living today. And there are many atrocities going on that may or may not end up in history books, but that I'm held accountable for, because I can find something to do to make a difference."

So we Indians must observe our society carefully. Speak up diligently. Love recklessly. Fight (non-violently but) boldly. Ultimately, what we choose to do today in preparation for tomorrow, and how we choose to view - or ignore - a rapidly changing world, will not only shape our lives, but also the legacy of India for years to come.

From THE INTERNATIONAL INDIAN, 6th Issue for 2008, Vol 15.6

Leave a Comment: