Narayan Wamanrao Tilak – Marathi Poet from Maharashtra

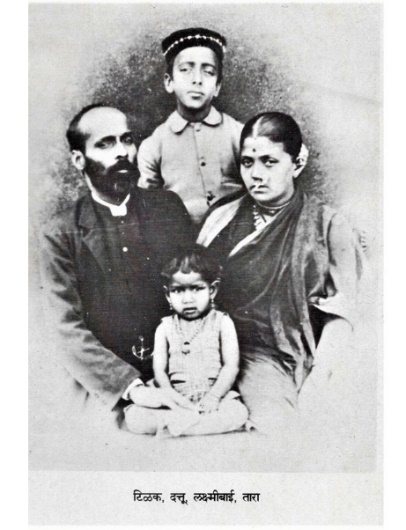

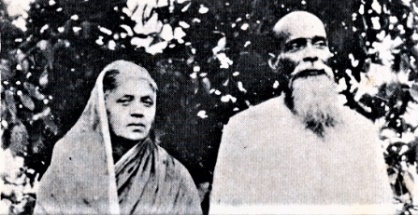

Narayan Wamanrao Tilak (1861-1919) and Laxmibai Tilak (1868-1936)

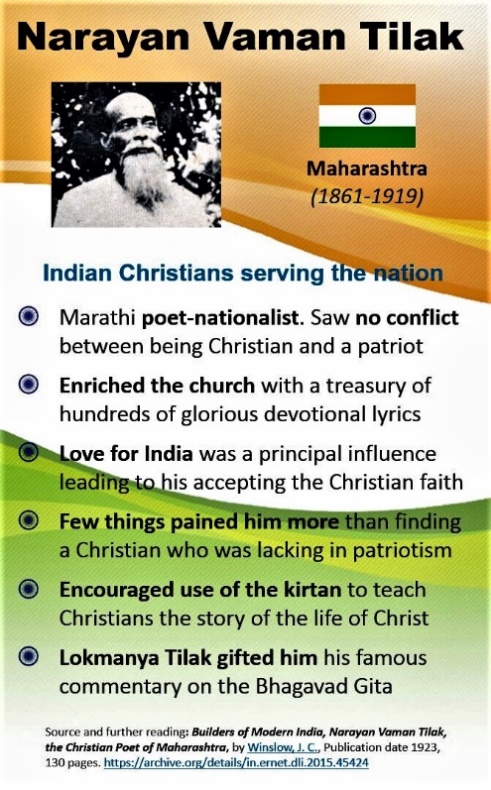

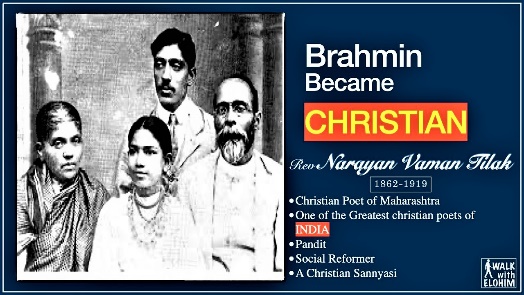

Narayan Waman Tilak, the renowned Marathi poet and a social reformer, is loved throughout Maharashtra as “the poet of children and flowers.” He was born into a Hindu Chitrapavan Brahmin family in Karajgaon village in the Ratnagiri District of Maharashtra on 6 December 1861.

Biographies of his life mention he was disliked by his father because he was born with feet first, which at that time was considered a bad omen in the Indian culture. During his education, he learned Sanskrit literature extensively. He later married to Manakaranika Gokhle, who then took the married name of Lakshmibai Tilak.

After completing his education, he took up several jobs in different places in Maharashtra such as a teacher, a Hindu priest and a press compositor.

In 1893, Tilak traveled by train from Nagpur to Rajanandgaon Sansthan in search of a new job. Rajanandgaon Sansthan, in those times, was a princely state in the Central Province of India. While on the train, he met a Christian missionary, who after a lengthy conversation, presented Tilak a copy of the Bible and whispered a “prophecy” in Tilak’s ears saying, “You Will Come Under The Grace Of Savior Jesus In Less Than Two Years.”

Tilak was very disappointed in the Hindu caste system, with its emphasis on rituals and ceremonies in Hinduism. He was drawn to the teachings of the Jesus Christ in the Gospels, and after a series of life changing events, he decided to follow Jesus Christ in 1895.

When Lakshmi bai heard about his decision, she was stunned. This led to a separation between the couple for some time. She started studying the Bible on her own and eventually felt the same interest and affection. She, too, accepted Jesus as her personal Savior in 1900.

The couple resumed their married life together. After accepting Christ, Tilak primarily lived in the town of Ahmadnagar and served about 24 years as a preacher in the local church, until his death in 1919.

Christ-Centered Work of Tilak

Tilak introduced using “Bhajans” and “Kirtan” to the Marathi church, enriching their devotional life by this art form familiar to them. He never gave up his Indian cultural birth right but brought the riches of Hindu heritage in to the Church.

Narayan Wamanrao Tilak has written more than 2100 poems, some of them comprising hundreds of lines. He also started to compose, in Marathi, an epic titled “Khristayana”, describing the works of Jesus Christ in native Indian form.

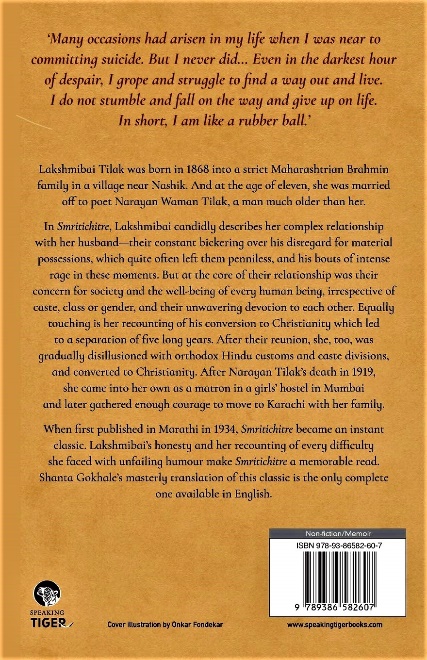

However, he died after finishing only ten of its chapters. Lakshmi bai later completed the epic by adding 64 chapters of her own. Laxmi bai also wrote her autobiography titled, “Smruti Chitre”, which was a masterpiece in Marathi literature. It was published in 1934-1937 in four parts.

Narayan Waman Tilak’s work in Christian literature and poetry in the Marathi language has been immense, yet sadly, much forgotten over time. However, his legacy and Christian influence still lives on in the many lives he touched through the love of Jesus Christ.

Source: Jeevanmarg

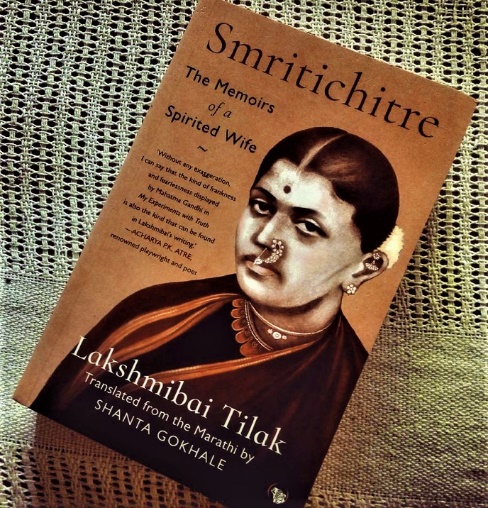

Part 2 Book Review: Smritichitre

The Memoirs of a Spirited Wife by Lakshmibai Tilak

Growing up in a Marathi-speaking household, I was long familiar with Lakshmibai Tilak’s Smritichitre. A personal narrative which was legendary for several reasons, I first heard of it from my grandmother and later from a large circle of extended family and friends who referred to it in whispers that ranged from the scandalized to the admiring and reverential.

In a regional culture which has had an abundance of feisty women, from bhakti poets to doughty warriors to social reformers, Lakshmibai’s life and outspoken revelations were all the more remarked for their singular facets and for the life of adventure and challenge she led while remaining a homemaker and mother. Originally begun at her son’s request and published in four parts between 1931 and 1936, Smritichitre gave Lakshmibai a visibility that her poetry alone may not have done.

Shanta Gokhale’s recent translation captures the essence of Lakshmibai’s iconic opus. Lakshmibai was a brave woman, a “spirited wife” as the title claims, but she was also by her own admission a self-taught one. Gokhale’s Introduction lists the liberties taken in translating this work and the editorial choices she made in excluding parts of the original and paraphrasing some of the poetry therein, decisions that are judicious and tighten what could otherwise have been an intimidating amount of detailing, some of which slips in regardless.

Lakshmibai was born in 1868, some 11 or 12 years after her grandfather was hanged during the 1857 revolt. Looking back she sees the event as having mentally unhinged her father Nana who became phobic about “pollution”, insisting on absurd ritualistic observances to preserve the family’s purity. “The woman in the kitchen, which was always Mother, had to do all the cooking in wet, freshly washed clothes and use only her right hand… The left arm had to hang by her side…”

Though all their neighbours were Brahmins, her mother had to follow them out if they called, “sprinkling water as they left.” She wryly notes that her mother and grandmother revolted at Nana’s excesses through little subterfuges, pretending to wash everything from grains to salt and sugar at his bidding, while her mother also used his absences to go make puran-polis in Maratha households – subterfuges not dissimilar to those with which women have defied patriarchal diktats through the ages.

Lakshmibai’s marriage to poet and controversial social reformer and activist Narayan Waman Tilak, or “Mr. Tilak” as she refers to him throughout , introduced her to a very different worldview.

A maverick who abhorred all forms of superstition and orthodoxy, Mr. Tilak was constantly locking horns with his father Mamanji who was given to being possessed by the goddess every Friday and had further made up his mind that his brother-in-law Mahadevbhauji, his son Mr. Tilak, and now Lakshmibai were demons sent to torment him.

Tilak’s unorthodoxy (he eventually converted to Christianity) did not preclude a touchiness which bordered on the absurd. He upped and left when offended, frequently disappearing for long stretches of time, was given to tantrums and violent outbursts (he threw his pregnant wife down the stairs after losing at dice), but also displayed genuine love and concern. Their uncommon partnership was rooted in mutual respect but Lakshmibai clearly bore the brunt of his eccentricities and the whimsicalities of those she had to depend on.

Not surprisingly she writes of being on the verge of suicide several times. Her conviction that women needed to be independent economically and the urge over time to do something useful with her life made her begin training as a nurse – something she had to, sadly, abandon even though she immersed herself in serving others in much the way Mr. Tilak did.

Lakshmibai’s courage was remarkable. This was a woman who moved to Karachi on being widowed and tried to make a new life there. A degree of family loyalty restrains her writing all through but she unsparingly records the prejudices she witnessed, of caste, faith, community and patriarchy.

The consequences of Mr. Tilak’s conversion to Christianity were predictable as were the social pressures exerted to ensure she did not emulate him or the eventual outrage when she did. The humiliation by those she loved, the loss of her children, battling the plague, and coping with the vagaries of a generous but impractical spouse could hardly have been easy. She is movingly upfront about her grief, guilt, and sense of disappointment but stops short of rancour and bitterness.

Like Pandita Ramabai’s earlier memoir, Smritichitre gives us glimpses of the lives of intelligent, questioning women and the tough choices they often faced at a time when the freedom struggle had ironically begun to attract women in large numbers. Though its roots are in autobiography it ends up becoming pretty much Mr. Tilak’s story, occasionally moving from straight recounting to introspection and analysis and giving us the kind of insights that make it easy to understand why Lakshmibai became such a legend.

In the final analysis, what sets Smritichitre apart is its readability and the careless ease with which Lakshmibai uses humour and irony in describing even her most grim ordeals.

Despite its being enumerative, descriptive and episodic for the most part; despite many of the episodes leading nowhere; and despite the repetition in much of the account, one reads it and returns to it with pleasure and interest. Impressionistic, minutely detailed, replete with minutiae triviae, it nonetheless holds the reader’s interest. This is as much due to the unique attributes of its principal players as to their times and the lives they led.

Vrinda Nabar is the author of “Caste as Woman” and a former Chair of English, Mumbai University.

Leave a Comment: