Even after 40 years, I can still remember having my fingerprints documented for my criminal record. It was the first time in my life I felt ashamed about anything.

The young police constable was pleasant and quiet-spoken as he gently guided me through the process of fingers, thumbs, and ink pads. He was at all times sensitive to the sense of grief originating from a single sound in the room: the uncontrollable weeping of my distraught mother as my father tried quietly calming her.

As recent immigrants to the UK from India, they were confused and stunned. They had wrenched themselves from established lives as schoolteachers. They had travelled to England by sea, and they had taken jobs working in a shoe factory and selling bus tickets. All so that my brother and I could get an education. For families immigrating from the Indian subcontinent, getting their kids educated was (and still is) the driving priority. So when my parents discovered that their teenage son had spent years secretly engaged in arson and shoplifting just “for fun,” they could barely comprehend it.

Sometimes it takes the tears of a loved one to stop us in our tracks and focus our minds on where we’ve gone wrong. But what exactly was I ashamed of? My mother’s grief had brought sudden clarity. I was suddenly clear about the damage I had caused to my family—shameful, lasting damage. It dawned on me that there really is a moral law in the universe, and I had over-stepped it. Actions had consequences, just as my family had taught me. The Hindu idea of karma is that you get what you deserve — and here was karma, spectacularly demonstrated.

A Six-Month Experiment

I am the son of a Hindu priest who was himself the son of a Hindu priest. In the working-class English town where I grew up, life revolved around our close-knit Indian community. We regularly met in temples or public halls to celebrate religious festivals and holidays. I never once heard the gospel in my first 18 years. My understanding had always been that “Christian” meant you were white and British, and no one ever suggested otherwise.

But then I left home for university and—by some divinely-orchestrated coincidence—got to know a bunch of Christians. To me, they were do-gooders: nice enough people who just didn’t have their heads screwed on straight when it came to being rational. At least that’s how it seemed from their arguments. They would take me along to these meetings where someone would present a Christian message or testimony. Afterwards, we would debate the (many) holes in their arguments. Despite my skepticism, these good Christian students adopted me as some kind of “project.” I didn’t share their faith, but their friendship and care moved me.

You see, there was always one roadblock on my journey to understanding Christianity, one concept that, in my view, was immoral and unacceptable: the idea of “grace.” The notion of someone else suffering shame and pain for the wrongs I had chalked up was absurd and repugnant. To me, grace and karma were complete opposites. Karma is logical; it feels right. It’s fair. Karma is what happened in the police station that day.

This attitude persisted for months, until, one day, one of my friends, Alex, commented thoughtfully, “Chris, you can argue forever about the unfairness of the cross. In many ways you’re absolutely right. Or, you can accept that this man Jesus died because he loves you. It’s up to you”.

Still carrying my doubts, I worked out a way to give this Christian thing a try: make the commitment, say the prayer, and see what happens over the next six months. I reckoned I would know in that time if it was true or not. What was there to lose?

The six months became 12 and then 24 (mainly because I continued to enjoy the social life of church). I graduated in engineering and began studying towards a Ph.D. But I was a lazy Christian. I barely picked up a Bible, prayer was an annoying afterthought, and I only went to church if I felt like it, which wasn’t often.

One day, my Anglican minister, David, made a suggestion. He said I should get baptized. I was appalled at the thought. Genuinely horrified. The exact words in my head were: “Baptism is something you Brits do to your babies—why are you talking to me about this?” I had seen infant baptisms on TV—was this fellow seriously suggesting wrapping me up in a white gown and dunking my head in a bowl?

Despite my recoiling, David persisted, and he showed me in Scripture where the baptism of adults appeared to take place. I was still unnerved by the whole thing. It sounded crazy. But David gently advised that I should make a decision: Accept the faith, all of it, or reject it. Eventually, I consented. And so, one quiet evening in March 1984, I found myself at the first baptism service I ever attended—my own. I still recall my bewilderment as I noticed the sprinkling of water falling from my head onto the pages of the service book in my hands and wondered, for a second, if I might get into trouble. I didn’t!

And God honored that small act of obedience.

The Wilderness Year

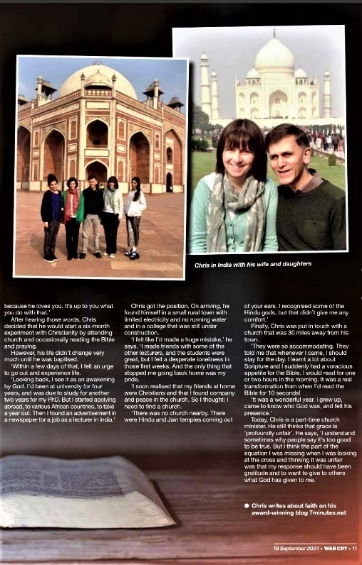

Much later, I would come to understand what a baptism of the Holy Spirit is, but at the time I only knew that within days, hours of that event, I felt a restless urge to quit studying and “do something different.” After a few unsuccessful applications for jobs in Zambia and Kenya, I got a position lecturing at an engineering college in India. A remote part of India where I had no contacts, and never having lived in the country myself.

I had grand ideas—mainly based on English college life—of what my sojourn in India would look like. However, it was nothing like that. The school, only partially built, was located in a remote part of the country. I was told to teach computing with no computers, and for several months I had a “laboratory” with nothing in it—just a bare room. Meanwhile, I lived in a small village outside the college town, in a humble dwelling with intermittent power, no running water, and freaky wildlife, including “snakes and scorpions” (Luke 10:19) wandering around outside.

Worst of all, I felt suddenly and terribly alone. Though eventually I made some truly great friends, those first few weeks were unbearably lonely. There was no church, and there were no other Christians. In short, I hated it. In the evenings, I could just see airplanes flying into the horizon toward distant lands. I dearly wished I was on board. There were frequent tears—I couldn’t understand what I was doing.

Later in my faith journey, I could see that this was a “wilderness” experience of the sort many other Christians have shared. It’s a model we receive from Jesus himself. Sometimes it’s exactly what God needs to break through a hard heart.

After some weeks, I discovered a small brethren fellowship that met in another town. Every Sunday morning, I would struggle to get on a packed bus to get to that town. Getting on a state-bus in India virtually involves a fight, And I distinctly heard God say: “Chris, when your fellowship was a short walk down the road in England, you couldn’t be bothered to go. Now you will fight to go.” I was broken, but I was also being re-made.

Those surprised and wonderful Indian Christians welcomed me from the day they set eyes on me. Every Sunday became an entire day at their house, complete with meals, conversations, love, and support. During those months, with their help, I grew enormously in faith. I began devouring Scripture—sometimes for hours in a day—and I discovered a God who wanted me to depend on him, a God who knew me and spoke to me. A God who wasn’t an experiment.

That year included another unexpected blessing: a chance to travel north overnight and meet my previously unknown set of cousins, aunts, and uncles. They are Christian. (My mother had actually given up her nominal Christian faith when she married my Hindu father.) And they were able to introduce me to a much wider range of Indian church experiences.

At the end of that year, on my return to the UK, folks in that small Anglican church (who had also supported me through the year with letters and recordings) barely recognized me. You’ve completely changed!” they would invariably say.

Still Bewildered By Grace

Since then, I have married my lovely Christian wife, Alison (I think she also adopted me as a project). We now have three wonderful daughters in their twenties. Around 10 years ago, while working in the telecommunications industry, I began training as a Baptist minister. Today, I help lead a small English church while keeping a part-time role in the tech world.

God has answered many prayers over the years, while leaving many others unanswered. We have endured our share of family crises, but in Christ I have an anchor in those storms that centres me back to where I need to be. If you’re looking for an easy ticket through life, the Christian faith isn’t it. But if you want purpose, meaning, and direction, here is a narrative, a grand story, in which you have your own essential part to play. And most importantly, you get the incomparable privilege of intimately knowing the Author. And in my regular writings, I now find myself confidently, and I hope convincingly, arguing the Christian worldview. Like those Christian students, I don’t have all the answers, but I do know that the Christian worldview answers life’s biggest questions more convincingly than any other.

I should say that my mother’s driving ambition was also fulfilled. I ended up with a bunch of university degrees—I really hope it makes up for that day in the police station! But she got more than she bargained for, becoming a Christian during her own life crisis, after my father left us in my teens amidst considerable family sadness. She passed away a few years ago as part of a loving, faithful congregation in that same small town where we grew up.

I don’t understand grace, even now. The cross is appallingly unfair. I suspect I’ll never have it entirely figured out, at least in this lifetime. But I’m thankful that because of God’s grace, I can love Him and commit my life to Him even as He—and His grace—lie outside my capacity to fathom.

Leave a Comment: